- Arts CornerFeaturing Richard Simpson

Richard Simpson

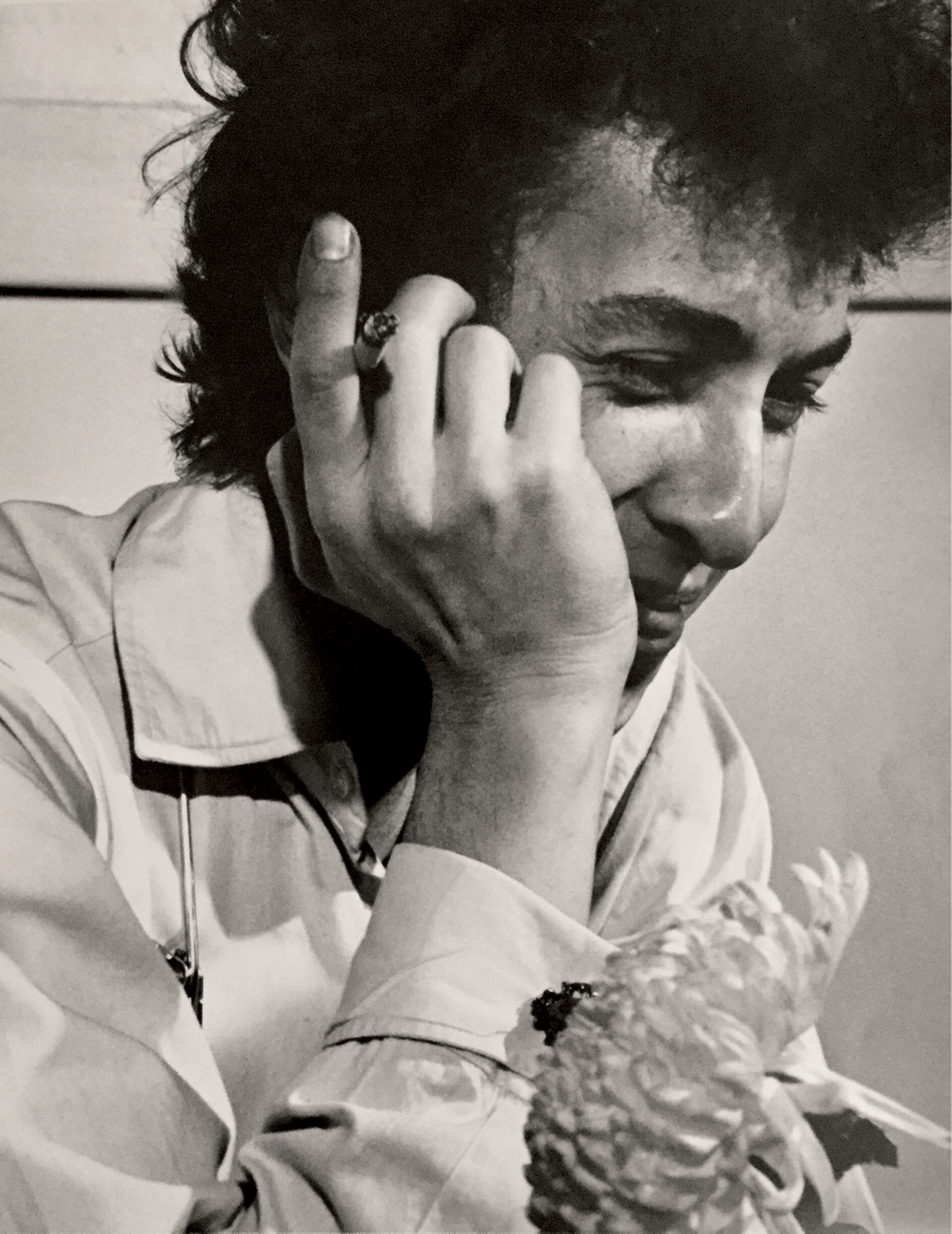

Bob Dylan Series

This series of Bob Dylan photographs was taken in 1964 at the Sacramento Memorial Auditorium, during a featured interview by Channel 10. Dylan was playing to a less than favorable audience because he was transitioning from folk to electric guitar.

Richard Simpson

Richard Simpson was born and raised on a Sierra Foothill cattle ranch in Northern California—property homesteaded by his great grandparents who had made the overland journey across the continent by Conestoga wagon in 1852.

Richard Simpson’s lifelong passion for black-and-white still photography and the sense of the “Decisive Moment” began at an early age. He has produced an archive of thousands of photographs recording images from rural farm life, Bob Dylan, the Korean War, California’s Mendocino Coast and American River Canyons, Sacramento’s Skid Row to a portrait history of Native American Maidu Indians.

In the 1960’s and ‘70s, Simpson worked as Director of Cinematography for KVIE, Channel 6 as a writer/producer/director/cinematographer/film editor/music composer/voice. He created eleven films which were televised nationally through NET, ETS, and PBS, and which were awarded grants from National Endowment for the Arts, Reader’s Digest Awards, Corporation for Public Broadcasting and NET.

During this period, Simpson was also employed as a cinematographer for the Peabody/Emmy award-winning BBC TV series, AMERICA (with Alistair Cooke) and the BBC/Time Life CHRONICLE series.

In 1977, his book OOTI, A Maidu Legacy was published by Celestial Arts. As anthropologist, photographer and writer, Simpson tells the story of the Maidu creation myth with photographs of Lizzie Enos, an elder tribal historian, preparing the stable acorn mush and bread. The powerful photographs and history have been reproduced and recorded widely.

Richard Simpson’s photographs have appeared in magazines, books, art galleries, and museums. He is in the permanents collections of Oakland Art Museum, California State Archives and Indian Museum, and several universities.

From 1980 to the present, Simpson works as a freelance photographer, writer, filmmakers, and sculptor residing in Northern California.

Interview Notes: Richard Simpson's Bob Dylan Photographs, Memorial Auditorium, 1964

As the still photographer, I had come to this film shoot being specifically interested at the time in the natural reactions of the face uninhibited by staging and direction, and how such an otherwise inactive plane related to the “Decisive Moment”, if at all. The answer for me was immediate, Dylan’s face seeming as open and un-posed as an Ansel Adams terrain, which changing subtleties of expression as unpredictable, quick and fleeting as an insect in flight.

Richard Simpson

Dylan’s mood and cigarette smoke swirls about him and us like ropes pulling us in together even tighter. We are seated in a small, drab, pale yellow room high above the concert stage from which Dylan has just left (41 years ago, come October 28, 2005) immediately following his first concert ever in the town of Sacramento. From the high balcony, not far from the room in which we now sit, I had only minutes before looked down to watch Dylan, spot lit upon the stage below—standing along, on spindly legs, and doing his songs. Though he seemed as fragile as an insect caught in that circle of light, Dylan’s songs were etched with power: a voice of conviction and urgent words echoing out over the darkened empty seats and into the black recesses of the cavernous Memorial Auditorium.Dylan’s mood and cigarette smoke swirls about him and us like ropes pulling us in together even tighter. We are seated in a small, drab, pale yellow room high above the concert stage from which Dylan has just left (41 years ago, come October 28, 2005) immediately following his first concert ever in the town of Sacramento. From the high balcony, not far from the room in which we now sit, I had only minutes before looked down to watch Dylan, spot lit upon the stage below—standing along, on spindly legs, and doing his songs. Though he seemed as fragile as an insect caught in that circle of light, Dylan’s songs were etched with power: a voice of conviction and urgent words echoing out over the darkened empty seats and into the black recesses of the cavernous Memorial Auditorium.

THE SACRAMENTO BEE’s art critic Bill Glackin had written two days later: “Something around 1,000 showed up.”

A most generous estimate since my recollection has Dylan singing his heart out to a very tiny crowd of no more than 300 standing fans, circled in and bellied-up to the stage-----a one night stand in a not-yet-so-hip for Dylan—town; next stop San Mateo; after that, going on up to Fort Bragg; Dylan’s first sojourn into the sticks of California.

But the starkness of an empty house had obviously held no power to dismay, for Dylan along with his body guard Bobby Neuwirth, arrived from the concert below charged with energy and humor, greeting the setting up of lights, mikes and film camera etc. for the planned local KXTV television interview with jokes and laughter; remaining at ease and in good spirits throughout the entire interview and its barrage of: “We’re here with BOB DYLAAAN,” America’s New Voice For Freedom and Individuality in Folk Music, of Woody Guthrie questions, Barry Goldwater jokes, concerns over income taxes “a la” Joan Baez, etc.

And though Dylan characteristically and deftly fielded all these questions, one answer did in fact break the surface. The question pertained to Dylan’s own song writing, and asked: “Do you consider the music you do or the lyrics that are in the music, the most important? What do you concentrate on the most?”

Dylan answered with a chuckle: “Well, I concentrate on really----really somewhere between those two things. The lyrics----the lyrics, they are just a vehicle. The guitar is just a vehicle for the lyrics, I would think. A lot of lyrics can’t be driven anywhere so they just don’t ever get in the car to be driven. That’s about all I can think of…

(Interviewer): What do you think about commercialism of folk music? Do you think it’s a good thin, or do you think…

(Dylan): I think it’s wonderful. I’m one hundred percent in favor of commercialism!

(Interviewer): Do you think that this has helped folk music by bringing it to the public eye so they can buy it then, and that therefore folk music has become a stronger art form----or do you think that it has been hurt by commercialism in any way at all?

(Dylan): Uh, I don’t think anything is really hurt by anything, you know, if people…

(Bobby Neuwirth): It can’t be hurt!

(Dylan): It can’t be hurt, right. It can be uh, (chuckle)----It can be slapped (chuckle). But you know, it can be uh, well you know, it can be dragged around a little bit, but I don’t see how it (commercialism) could possibly hurt it.

(Here the interviewer {Dick Cruiser, an accomplished folk singer himself who plays the twelve string guitar} mentions Dylan’s songs as controversial social commentary, Dylan taking a liberal stand in his belief that human rights and civil liberties----asking Dylan: “Don’t you try to define these things in your lyrics?”)

(Dylan): I believe in liberalizing and human rights (chuckle), whatever they are. No, I don’t think I try to define it.

(Interviewer): You just comment in other words, on what you feel perhaps is wrong or unfair or---

(Dylan): Well, I just make a picture, you know, of what’s there. If it’s there, you know, if you want to call it human rights, well you can call it human rights I guess. But, I just comment on what’s there.

(Interviewer): In other words then----you’re telling a story and this is the essence of folk music to you, or----do you think you can create any good by telling in the story that people should be equalized for instance, just in human rights?

(Bobby Neuwirth): People gotta make up their own mind!

(Dylan): Yea.

(Interviewer): You wouldn’t try to make up their own mind for them, you just talk about it.

(Bobby Neuwirth): No—no.

(Dylan): For me to make up their minds---- I couldn’t do that; I would have to live their life. If I were to make up their mind, and you know, I would have to lead them somewhere----which I can’t. The world is small enough as it is, you know. I can’t uh,-------BARBARA SAILS!

A commotion at the door. A young woman bursts into the room brandishing white chrysanthemums clutched in her hand----a local girl from Davis.

“Come in!---sit down----you’re on Television!” calls out Dylan, seemingly pleased with the interruption.

Momentary confusion and shifting of position.

(Interviewer): Hello Barbara, I think we’ve met in Davis. What is your name?

(Girl): Barbara. Barbara Madell.

(Interviewer): You said it was Sails.

(Girl): Well, Barbara Sails-Madell----hyphenated.

(Interviewer): Did you ever write a song about Barbara, Bob?

(Dylan): Huh?

(Interviewer): Did you ever write a song about Barbara?

(Dylan): Barbara? Lot’a Barbaras-----she was uh-----

Barbara’s hurricane entrance had hit shore and come inland. The interview stalls, flounders and fades to its inevitable end. And suddenly, Dylan with his small and happy entourage in tow, takes flight from the tiny yellow room-----leaving us behind as he had come in, laughing, on his way to immortality.

Interested in exhibiting your artwork at Cloud Forest Cafe?

© 2014